The Yoruba Rythmic Deities: A Brief Analysis of Chucho Valdés’s Use Of Yoruba Rhythms related to My Own Performance Practice

Rafael Zaldivar

Université Laval

Summary

Yoruba rhythms have been an endless source of inspiration to musicians around the world since their African birth (Acosta 2003, 59). As the Yoruba religion has played a major role in shaping Cuban culture since the massive arrival of West African slaves on the island in the nineteenth century, a multitude of Cuban instrumentalists and composers have shown undeniable Yoruba influences (Ortiz 1973, 12). Chucho Valdés is one of the most famous figures to illustrate this phenomenon (Acosta 2003, 212). For more than five decades, he has performed, improvised, arranged, composed, mixed, mastered and edited music that not only uses Yoruba rhythms but also strongly celebrates the general Afro-Cuban legacy.1 Valdés is a pioneer and model to most Cuban musicians, including myself, because he has developed a unique and personal style through the hybridization of two powerful and distinct musical genres: jazz and Afro-Cuban music (Acosta 2003, 212). I have been greatly influenced by this pianist since I started learning music, and I believe I have been following his path in my recent quest for hybrid creative music. In this essay, I will discuss the personality of the Yoruba deities in relationship with their rhythms. Then, I will do a brief analysis of Chucho Valdés’s performance practice and use of Yoruba rhythms. Finally, I will tend to in related Chucho’s approach to my own approach. I will attempt to define and analyze both ways of approaching piano performance, improvisation, and composition and will illustrate the main differences. I will then explain why I have chosen this musical direction and sketch out my personal path within the broader perspective of contemporary jazz performance practice.

The Sacred Hierarchy of Yoruba Rhythmic Deities

According to Samuel Johnson and Johnson Obadiah, the term Yoruba comes from the word Yarba, an area located in West Africa where the Yoruba tribes settled permanently (Johnson and Obadiah 1966, 6). Yoruba believers say that he invented the universe and represents the beginning of cosmic energy (Castellanos and Castellanos 1992, 18). Olodumare generated a son who is the creator of human life on earth: old Obatalá. The son transmitted his father’s intelligence to men and represents both human purity and peace through the white color (Castellanos and Castellanos 1992, 26 –27). Obatalá then created the goddess Yemayá, who is the most respected figure among the Yoruba gods (Castellanos and Castellanos 1992, 53). According to the mythology, she represents the gift of female motherhood through the maternal water principle (Castellanos and Castellanos 1992, 53). Her blue color represents the depth of the sea, where she and Obatalá gave birth to their son the god of human consciousness, the messenger Ellegua, who informs the gods and judges the beginning and the end of humans’ lives (Ortiz 1973, 39). Ellegua’s red and black colors symbolize human blood and human souls’ death and darkness.2 Fernando Ortiz associates Ellegua with human beings’ own perception of life and consciousness (Ortiz 1973, 39). Ellegua’s reputation as the good messenger contrasts with the attributes of his brother the war god Ogun. A patakí (a story from the Yoruba mythology) says that the latter raped his mother (Yemayá) (Castellanos and Castellanos 1992, 33).

Fortunately, Ellegua told his father (Obatalá) about this, and the creator of human life punished Ogun for his unscrupulous darkness by forcing him to remain isolated in the green forest (Castellanos and Castellanos 1992, 34). Going through such punishment, Ogun needed help from his brother, the god of hunting Oschó-oshí, who provided him with food (Ortiz 1973, 34). Oschó-oshí’s attributes of hunter and helper are represented by the purple color (Castellanos and Castellanos 1992, 36). Castellanos explains that the trinity Ellegua–Ogun–Oschó-oshí symbolizes a strong union in the Yoruba religion. These three also comprise the final main deities of its Pantheon (Schweitzer 2013, 27). However, I will focus on Obatalá (the old male god of human creation) and Yemayá’s (the old goddess of the sea) sacred rhythmicality because they represent the most powerful gods on earth and are celebrated more frequently through artistic manifestations (Castellanos and Castellanos 1992, 26–57).

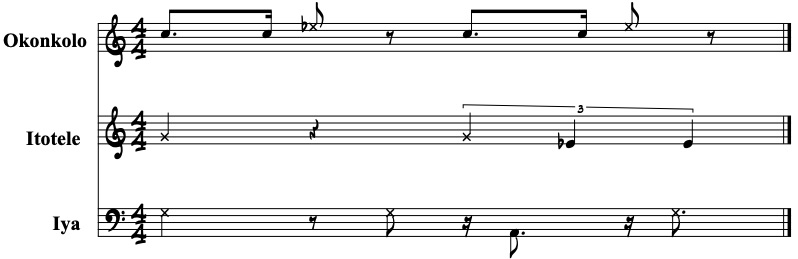

Obatalá’s ancient and sagacious personality is represented rhythmically through a slow tempo (Delgado 2001, 324). His music is usually performed in a forte dynamic with a tough and rough sound. These characteristics, as well as a high level of density, reflect the god’s ultimate power on earth and his masculinity (Delgado 2001, 320). Yemayá’s typically softer dynamic, long and resonating pitches, and ocean-like sense of flow evoke both her femininity and maternity. Her rhythms are light and sparse and are traditionally played in a slow-to-medium tempo. Both the Obatalá and Yemayá rhythms are performed in a 4/4 meter by a set of three different drums called batás (Schweitzer 2013, 33). Each batá has two different pitches, which vary in size and function (Schweitzer 2013, 27). Example 1 shows the traditional Yemayá rhythm. As illustrated below, the lowest batá, called Iya (mother), carries the leading melody and usually has the more active part. In this case, it uses an intricate combination of downbeats and both eighth-note and sixteenth-note upbeats. The middle batá, called Itotele (mediator), emphasizes the first and third beats with its highest pitch while the low one creates a countermelody that follows a quarter-note triplet figure in the second half of the measure. The smallest batá’s name is Okonkolo (son). Its role is to maintain a steady pulse, which, in this case, alternates between the low and high pitches.

Example 1: Abbilona Large Ensemble, Yemayá 3

Example 2 illustrates the well-known Obatalá rhythm. From the lowest pitch of Iya, more activity and, therefore, increased density can be observed. It reinforces the first beat of the measure with its lowest pitch while the higher one plays a two-three-clave pattern that contrasts in timbre. The second and fourth beats of the measure are emphasized by the low tone of Itotele, which is complemented by the high pitch with a constant syncopated pattern on the upbeats. Once again, Okonkolo has a metronomic role and emphasizes every beat with its highest pitch while the lowest tone supports the Iya motive with sixteenth notes played before every second and fourth beat.

Example 2: Abbilona Large Ensemble, Obatalá 4

The Obatalá and Yemayá rhythms both involve polyphonic and polyrhythmic traits as the various pitches interact melodically and rhythmically in a way that evokes collective exchange and, to some extent, dialogues between humans and their gods. The contrast between high and low tones enriches these melodic implications, strengthens the pulse, and produces a complex interaction between six distinct notes. Such interactions also imply a variety of timbres, and the overall result is a cyclical polyphonic wave of rhythms.

Chucho Valdés’ performance practice and use of Yoruba rhythms

Chucho Valdés was born on October 9, 1941 in Quivican, Havana. Chucho’s early artistic career survived during a period of a political transition in Cuba.5 According to Leonardo Acosta, most American and Cuban popular musical genres were banned with the triumph of the Cuban revolution on January 1, 1959 (Acosta 2002, 97). Jazz, rock, and new trova were prohibited on academic music centers, television and radio (Acosta 2002, 97). For example, The Monday’s Jazz Radio Show was sabotaged by The Musicians’ Union that imposed fines and sanctions to performers who participated in this program (Acosta 2002, 97). Nonetheless, many jazz combos emerged despite the prohibitions imposed by the Cuban revolution (Acosta 2002, 100). They are The Peruchín Jústiz Trio, The Five, The Batcha, The Fantastic, and The Chucho Valdés Group among others (Acosta 2002, 100). I have always admired Chucho Valdés for his virtuosity, his courage, and his undeniable ability to survive with his rhythmic identity. From his first albums, he knew how to take advantage of the popular American trends of his time without leaving his musical roots aside.6 He brilliantly incorporated Afro-Cuban elements into the already hybrid Afro-American fusion genre and surprised the world when he came up with the 11-piece group Irakere, which offered a new vision of musical synthesis.7 Chucho Valdés success and efficiency partially reside on his awareness of the importance of analyzing and internalizing one or more jazz pioneers’ language before attempting to innovate within this genre (Panken 2011). Indeed, his piano and improvisation styles appear to come from a deep understanding and assimilation of the jazz great Art Tatum (Berendt 2009, 716).

Leonardo Acosta’s idea that cultural exchange can only happen through the internalization of elements from two different musical traditions seems to correspond to the Valdés’ journey (Acosta 2003, 90). He points out that this phenomenon can only result from a long process of archiving both traditions before it can result in a real cultural symbiosis:

In the United States as well as in Cuba, jazz musicians always lived in two different worlds, and at certain times in jazz history the one most important and favorable to creativity and the development of the musicians themselves has been that “other world” of the jam sessions, as the British sociologist Francis Newton has intelligently suggested. But because our jazz musicians have been so strongly rooted and well trained in the Cuban (or Afro-Cuban) tradition, three things would gradually and almost imperceptibly occur with respect to their understanding, assimilation, and interpretation of jazz: (1) The soloists, on wind as well as string instruments and piano, would progressively come to master the phrasing, diction, and rhythmic sense of both types of music, until they gradually combined the two into one common language. (2) Cuban percussion would slowly adapt itself to jazz arrangements and occasionally it would be the other way around, and the arrangements were written using the polyrhythmic elements of our music as a base. (3) The arrangers would incorporate elements taken from jazz into their orchestrations of Cuban numbers of all genres and into their own compositions. (Acosta 2003, 59)

A sense of cultural identity and artistic needs have undoubtedly motivated and shaped Valdés’ performance practice. However, it seems as though his hybridization process came from a desire to revive the idiomatic material of a specific set of instruments: batás. Such instruments are traditionally found in Yoruba music, which is inextricably linked to the Yoruba religion. It is well known that Chucho Valdés has studied and practices this religion and considers himself to be a spiritual babalao.8 “In my case, Cuban religion was something I saw in my neighbourhood since I was a child and I decided to introduce. These were elements that I already had inside me,” says the pianist (Fuente 2015). Some critics argue that commercial motives are hidden behind the composer’s unique style in addition to his religious background. This is the view of Ernesto Jr. Portillo, who states that the famous pianist has been seeking commercial success by sticking to the original sound of Irakere’s debut since he won his first Grammy award (Portillo Jr. 2015).

According to Leonardo Acosta, Valdés’ compositional innovations basically involve superimposing preexistent Afro-Cuban rhythmic patterns and jazz devices, such as a walking bass or an improvised bebop melody, as well as combining binary and ternary metrics (4/4, 6/8, and 3/4) within the same thematic elaboration (Acosta 2015). Chucho Valdés’ musical synthesis was considered to be new during the 1970s and strongly contributed to consolidating Afro-Cuban Jazz as a musical idiom (Acosta 2015). However, Acosta also points out that Yoruba rhythmic integrations already existed as a performance practice (Acosta 2003, 212), and he highlights the compositional work of saxophonist Nicolás Reinoso and his ensemble AfroCuba (Acosta 2003, 225):

“AfroCuba had to fight against one of our deeply entrenched habits: In a basically noncompetitive society, we have and allow only one idol in boxing, one in baseball, one ballerina, one poet, one novelist, one painter, one concert guitarist, and another one on piano, to the exclusion of all the rest, who will arrive late or never to this imitation of Mount Olympus. [...] Since Irakere had already achieved such great success throughout the world, why do we need a rival group? This was most probably the bureaucrat’s point of view. The logical corollary would be to ask them to do something different, which would make sense if one group was copying the other, but in fact, AfroCuba was doing something different, and in some respect, it was more advanced than Irakere.” (Acosta 2003, 225)

Nevertheless, Chucho Valdés undoubtedly created a distinct musical product with his ensemble Irakere. His performance practice usually included a) original Yoruba polyrhythms played on traditional instruments, b) intact Yoruba melodies (often sung by vocalists), c) jazz harmonies, d) jazz timbres and instruments, and e) extensive improvisations using both Afro-Cuban and jazz devices.9

My own approach and use of Yoruba rhythms compared to Chucho Valdés’s work

Chucho Valdés and I both share the same cultural background and were raised as well as musically trained in the same country, which can explain certain similarities in our music. In addition to our obvious interest in jazz and Afro-Cuban music, I am concerned about reflecting my perspective of today’s world, just as I believe he was at the beginning of his career (Panken 2011). As we are now in a different period, such a concern guides me towards contemporary classical harmony, pop’s melodies, and modern jazz theories rather than jazz rock and fusion. Likewise, I completely agree that it is essential to internalize at least one of jazz’s great languages before manipulating the genre for purposes of hybridization. Even though I deeply admire Art Tatum’s piano style, I rather chose to study Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk in depth throughout my preparation years.

Except for our sense of cultural identity, I think the underlying motivations of my performance practice are not the same as Valdés’ motivations. First, I am more and more interested in research because of my love for music performance practice, my doctoral studies, and my emerging needs as a university professor. The field is also much less wide open than it used to be in terms of mixing elements from diverse cultures, which forces me to develop research abilities in order to innovate musically. My approach could therefore be described as more intellectual and less spiritual than that of Chucho Valdés.10 On the other hand, I am fully aware that a kind of survival instinct is hiding behind most of my musical directions. Indeed, working on creative ways to incorporate Yoruba rhythms into my jazz compositions connects me to my roots on a daily basis even though I have been living in Canada for 18 years. My usual instrumentation choices also distinguish me from Valdés, since I primarily focus on piano trio (piano, bass, and drums) or quartet (adding percussion). I think that there are many things I can experiment with in these small ensemble formats that allow the piano to be the main leading voice. Such instrument settings individually inevitably lead to a different writing approach compared to the international figure’s large ensembles.

As a matter of fact, I perceive many differences in the way Valdés and I conceive our hybridization process. First, I like to transform Yoruba rhythms, as I see each of them as a cell that can be manipulated in order to change its role, interaction, and meaning, and eventually get a “new” polyrhythmic result (always coming from an old source, of course). Secondly, the original or metamorphosed Yoruba rhythms I use are seldom played on traditional instruments. They are even often transposed into melodic material that can be heard on bass and/or piano.11 As opposed to Valdés’ content, the melodies I write are sometimes inspired by but are not restricted to the Yoruba tradition, for they sometimes come instead from jazz backgrounds.12 Furthermore, most of my compositions are based on current jazz harmony and include concepts from contemporary classical music as well as the M-base atonal axis-based vision.13 Finally, improvisation has a central function in my music, as indeed it does in the music of our Cuban musical ambassador.14

Reasons for my chosen path and its relation to current practice

There are several differences between Chucho Valdés’ approach and mine. I believe most of them can be explained by two essential factors: a) Valdés and I grew up and started our artistic careers during very distinct periods; and b) his integration of Yoruba rhythms seems to have been motivated by religious beliefs and commercial success, whereas I think my work is driven rather by my research interests and adaptation needs. My aesthetic choices are directly linked to current performance practice, since, not unlike my peers, I want my music to reflect the world as I see it now. I particularly embrace Steve Coleman's M-Base philosophy because I believe it opens my mind and helps me to express my ideas with a twenty-first-century vision that includes multicultural and universal awareness.15 I therefore explore some of Coleman’s melodic concepts in my improvisations and use quite a similar rhythmic approach in my compositions as I transform preexistent material to come up with “new” polyrhythms. I believe such an approach fulfills both my desire to conduct research and offers a kind of musical innovation throughout my career. I am also particularly interested in contributing to the creation of high-quality jazz music that incorporates Afro-Cuban material, which helps me to stay connected with my Cuban roots. For this reason, I try to keep in touch with and follow the careers of colleagues who seem to be pursuing similar goals, such as Danilo Perez16, Francisco Mela17, David Virelles18, Hilario Duran19, and Luis Deniz Gonzalez.20 Listening to their projects and sharing ideas with them are part of my creative process and, therefore, influence some of my deep motivations, artistic ideals, and musical choices.

References

Acosta, Leonardo. Cubano Be, Cubano Bop: One Hundred Years of Jazz in Cuba. Washington: Smithsonian Books, 2003, p. 59.

Acosta, Leonardo. 2015. “Chucho Valdés: Opiniones.” EcuRed. Accessed on Saturday, October 13, 2023. http://www.ecured.cu/index.php/ChuchoValdés.

Acosta, Leonardo. Descarga número dos: el jazz en Cuba 1950-2000. Habana: Ediciones Union, 2002, p. 1-100.

Berendt, Joachim-Ernst. The Jazz Book: From Ragtime to the 21st Century. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2009, p. 716.

Castellanos, Jorge and Isabel Castellanos. Cultura Afrocubana 3: Las Religiones y Las Lenguas. Florida: Ediciones Universal, 1992, p. 18.

Chucho Valdés’s Website. “Biography.” Accessed on October 9, 2023. http://www.valdeschucho.com/index.html#about.

Cubalatina website. “700 Indiens comanches déportés à Cuba.” Accessed on October 15, 2023. http://www.cubalatina.com/portraits/chucho-valdes.php3#.ViE3Utb-9SV.

Delgado, Kevin Miguel. “Iyesa: Afro-Cuban Music and Culture in Contemporary Cuba.” PhD dissertation, University of California, 2001. ProQuest (UMI 3026270), p. 324.

EcuRed. Accessed on November 9, 2015. http://www.ecured.cu/Irakere.

Fuente, U. “Chucho Valdés: Cuando toco el piano se sienten los tambores cubanos.” In La Razón journal, published on July 10, 2015. Accessed on October 15, 2023.

Johnson, Samuel and Johnson Obadiah. The History of the Yorubas: From the Earliest Times to the Beginning of the British Protectorate. London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1966, p. 6.

León, Argeliers. Del Canto y el Tiempo. La Habana : Editorial Pueblo y Educación, 1981, p. 38.

López, Irian and Dagoberto González. Abbilona Tambor Yoruba: Obatalá. Abbilona Large Ensemble. Irian López. Bis Music BIS 326, 1999, 1 compact disc.

Ortiz, Fernando. Los Negros Brujos. Miami, Florida: Ediciones Universales,1973, p.12.

Panken, Ted’s Blog. “Chucho Valdés Is 71 Today: A 2004 Downbeat Feature.” October, 9, 2023. Accessed on November 9, 2015. https://tedpanken.wordpress.com/2011/10/09/chucho-valdes-is-71-today-a-2002- downbeat-feature/.

Portillo Jr., Ernesto. Cuban jazz pianist Chucho Valdés recreates Irakere. Published on October 15, 2023. Accessed on October 15, 2015. http://tucson.com/entertainment/music/cuban-jazz-pianist-chucho-valdes-recreates-irakere/article_f572ccc9-ffe0-5850-bee9-de154b5ef618.html.

Schweitzer, Kenneth. “The Artistry of Afro-Cuban Batá Drumming” Aesthetics, Transmission, Bonding, and Creativity.” University of Mississippi, 2013, p. 27.

Steve Coleman’s M-base website. “Essays.” Accessed on November 10, 2023. http://m-base.com/essays/.

Valdés, Chucho. Irakere: Juana 1600. Chucho Valdés Large Ensemble. Chucho Valdés. Areito, LD-3660, 1976. 1 LP Album.

Zaldivar, Rafael. Drawing. Rafael Zaldivar Quintet with Zaldivar (p), Greg Osby (as), Lisanne Tremblay (vln), Rémi-Jean LeBlanc (b), Philipp Melanson (d), Eugenio Osorio (perc). Rafael Zaldivar and Alain Bédard. FND 119, 2012, 1 compact disc.

Zaldivar, Rafael. Farahon. Rafael Zaldivar Quintet with Zaldivar (p), Janis Steprans (s), Gabriel Hamel (g), Adrian Vedady (b), and Louis-Vincent Hamel (d). Rafael Zaldivar, 2015, demo recording.

See Chucho Valdés’s Website, “Biography” (Accessed on November 9, 2015): http://www.Valdéschucho.com/index.html#about.↩︎

See EcuRed’s website (Accessed on November 9, 2015): http://www.ecured.cu/index.php/Elegguá.↩︎

López, Irian and Dagoberto González. 1999. Abbilona Tambor Yoruba: Obatalá. Abbilona Large Ensemble. Irian López. Bis Music BIS 326, 1 compact disc.↩︎

López, Irian and Dagoberto González. Idem.↩︎

See Chucho Valdés’s Website, “Biography.” (Accessed on April 10, 2024): http://www.Valdéschucho.com/index.html#about.↩︎

Idem.↩︎

See EcuRed (Accessed on November 9, 2015): http://www.ecured.cu/Irakere.↩︎

See Cubalatina website, “700 Indiens comanches déportés à Cuba” (Accessed on October 15, 2015): http://www.cubalatina.com/portraits/chucho-Valdés.php3#.ViE3Utb-9SV.↩︎

Valdés, Chucho. 1976. Irakere: Juana 1600. Chucho Valdés Large Ensemble. Chucho Valdés. Areito, LD-3660, 1 LP Album.↩︎

Zaldivar, Rafael. 2012. Drawing. Rafael Zaldivar Quintet with Zaldivar (p), Greg Osby (as), Lisanne Tremblay (vln), Rémi-Jean LeBlanc (b), Philipp Melanson (d), Eugenio Osorio (perc). Rafael Zaldivar and Alain Bédard. FND 119, 1 compact disc.↩︎

Zaldivar, Rafael. 2015. Farahon. Rafael Zaldivar Quintet with Zaldivar (p), Janis Steprans (s), Gabriel Hamel (g), Adrian Vedady (b), and Louis-Vincent Hamel (d). Rafael Zaldivar, demo recording.↩︎

Zaldivar, Rafael. 2012. Drawing.↩︎

Zaldivar, Rafael. 2012. “Rule of Third.” Drawing.↩︎

Zaldivar, Rafael. 2012. Drawing.↩︎

See Steve Coleman’s M-base website, “Essays” (Accessed on November 10, 2015): http://m-base.com/essays/.↩︎

See Danilo Perez’s website, “Biography” (Accessed on November 10, 2015): http://www.daniloperez.com/aboutdanilo2/.↩︎

Radio Canada. “Rafael Zaldivar en concert à l’Astral.” Rafael Zaldivar Trio with Francisco Mela (d) and Morgan Moore (b). Accessed on November 10, 2015. http://musique.radio-canada.ca/concerts_evenements/revelations_musicales_2010_2011/rafael_zaldivar.asp.↩︎

See David Virelles’s website (Accessed on November 10, 2015): http://www.davidvirelles.com.↩︎

See Hilario Duran’s website (Accessed on November 10, 2015): http://www.hilarioduran.com/index.htm.↩︎

See Virelles, David. “Rimouski Jazz Festival.” Youtube Video. David Virelles Quintet with Luis Gonzalez Denis (s), Devon Henderson (b), Ethan Ardelli (d), and Luis Obregoso (prc).↩︎

Musiques : Recherches interdisciplinaires 1, n°1